Electric vehicles (EVs) feel too good to be true to many, but to others it’s simply not worth the risk/investment.

EVs have captured the public imagination as the future of mobility. They promise cleaner air, cheaper running costs, and freedom from volatile fuel prices. In Malaysia there are special incentives that bring their pricing down significantly compared to imported vehicles with internal combustion vehicles. Yet behind the hype lies a more complicated reality: for some households, EVs are a genuine escape route from rising costs and emissions; for others, they are an expensive trap.

So, are EVs really the path to liberation, or do they come with hidden limitations? Let’s explore both sides of the road.

The Good

Energy Independence and Sustainability

One of the strongest arguments in favour of EVs is energy independence. As solar panels become increasingly affordable, homeowners can combine renewable energy with an electric car to cut fuel bills to almost zero. Imagine charging your car directly from the sun and never stopping at a petrol station again. This not only reduces household expenses, but also supports a more sustainable lifestyle.

EVs also play a role in reducing carbon emissions. For eco-conscious families, replacing petrol with clean electricity is a tangible step toward combating climate change. Even in regions where electricity grids still rely on fossil fuels, EVs tend to emit less over their lifetime compared to combustion cars.

EVs as “Third Spaces”

Automakers now position electric vehicles as more than just machines for transport. Many EVs are designed as “third spaces” between home and work: quiet, air-conditioned cabins with large infotainment screens, USB ports for charging phones, tablets and even laptops, plus reclining seats and in some cases 5G connectivity.

This means an EV can double as a mobile office or lounge. Instead of paying for parking and overpriced coffee while waiting for an appointment, you could work from the comfort of your car. For freelancers, remote workers, and commuters, this flexibility adds a new dimension to vehicle ownership. Even if it’s waiting for your spouse or kids, an EV puts you in an office or relaxation space wherever you need it.

Shielding Against Fuel Price Volatility

Governments worldwide are beginning to phase out blanket petrol subsidies. In Malaysia, the removal of the RON95 subsidy is on the horizon, with targeted subsidies expected to reduce benefits for higher-income households. When petrol costs climb from RM150 per month to potentially RM250–300, EVs become more attractive.

Charging an EV at home is still cheaper than refuelling at the pump, and when paired with solar energy, the cost per kilometre approaches zero. For families concerned about fluctuating fuel prices, EVs offer a sense of stability and long-term security.

Removing Maintenance Worries

An aspect of car ownership that often goes ignored is maintenance costs. Many desirable premium vehicles are often very costly to maintain and run. A typical turbocharged, high-performance petrol engine consists of tens of thousands of individual parts, many of which are deeply integrated and highly complex – requiring expensive replacement rather than simple tuning or repairs that cars prior to the 2000s could be sorted out with. With new car purchases, some manufacturers even take advantage of the pricing of certain wear & tear items, such as brake pads and tyres in order to make more money from the aftersales side of the equation. With an EV, brake pads are often there just for emergencies, as regenerative braking can take care of most stopping power requirements.

Emergency Power

In Malaysia, we are blessed as natural disasters are relatively rare and usually not quite extremely devastating. The floods can still be particularly deadly and costly, and should the climate worsen we can only expect things to get worse. An EV is not going to serve as an escape vehicle, let’s be clear. However, many EVs can deliver Vehicle-To-Load (V2L) functionality, which means that you could use your vehicle to temporarily power large appliances such as electric stoves, kettles, and even fridges if need be. Most EVs that have V2L capabilities can provide enough power to keep a household going for days on end with a full charge. So while it is a very fringe use-case, we know it does come in handy in places like Japan where earthquakes and tsunamis can cut local power.

Escaping The Cycle

For decades the same handful of mostly Western brands have held a monopoly over what is considered premium in the automotive industry. Design trends, performance benchmarks, technological advancements – these were the things that separated the mass market from the premium. Well, with EVs – particularly Chinese EVs that escape taxation, the spell has been lifted and the cycle has been broken. Today many sub-RM200K EVs can out perform premium petrol-powered peers costing 1.5X as much. Even if you don’t particularly love EVs, buying one instead of a typical European sports sedan today means you have a chance to NOT pay the government enormous tariffs for your next high-status car.

The Bad

High Upfront Cost vs. Modest Savings

For all their advantages, EVs come with significant financial barriers. In Malaysia, the cheapest new EVs cost around RM100,000, compared to used petrol cars that may already be fully paid off.

Here’s the problem: if you drive only 1,000–2,000 km a year, your annual petrol bill may be just RM1,200–2,400. Even if fuel costs double, it would take decades of savings to justify the expense of an RM100,000 EV. Financing that purchase through a nine-year loan at 3% interest could cost around RM1,050 per month, or RM12,600 per year. Even if you save RM3,000 in fuel, you’re still losing close to RM10,000 annually.

In short, EVs only make financial sense for households that drive often enough to offset their higher purchase price.

Paying a Premium to Solve Small Problems

Yes, an EV can act as a mobile office, but let’s be realistic. Skipping one RM20 café session per month saves just RM240 a year. Compare that with thousands of ringgit in annual loan repayments, and the equation quickly looks lopsided. For most drivers, the “third space” benefit is more of a luxury than a necessity.

Low Mileage Households Don’t Benefit

Many Malaysian households simply don’t drive enough to justify an EV. Retirees, for example, may own petrol cars that are fully paid off and with low mileage. With such low mileage, the fuel savings from switching to an EV are negligible.

For these households, keeping a paid-off petrol car running for another 5–10 years is far cheaper than buying a new EV.

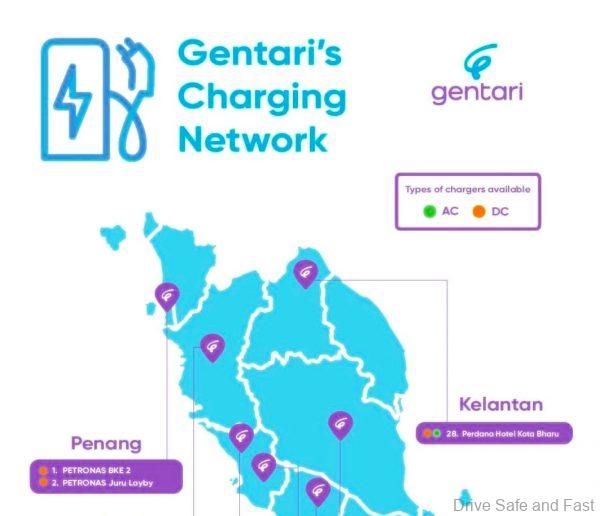

Charging Infrastructure Gaps

Infrastructure remains a critical obstacle. Many Malaysians live in condominiums or apartments without dedicated EV chargers, not even a 3-pin plug for overnight charging. Installing chargers is expensive and often not possible in older buildings.

This forces EV owners to rely on public charging points, typically in malls or office complexes. While convenient for some, it adds time, hassle, and cost—eroding the very convenience EVs are meant to deliver.

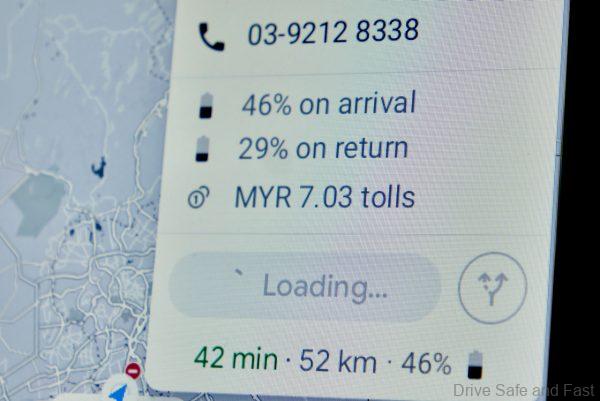

Mobility Without Freedom

There’s something fundamentally liberating about the petrol (or diesel) car experience. It doesn’t matter how old the car is either. My first car, a hand-me-down Corolla was older than I was by 5 years when I took it on a cross-country tour. There was no planning involved, just jump in, fill up and drive wherever. You just can’t do that with an EV. Sure, interstate trips are perfectly viable – but you can’t just get up and go wherever, whenever. Some degree of planning must be done to minimize down time and cost. Suddenly the vehicle goes from symbolizing freedom to becoming a game of logistics.

Depreciation Risks

The EV market is still evolving rapidly, with new battery technologies and government incentives reshaping the landscape every year. Buying an EV today comes with the risk of accelerated depreciation if a cheaper, longer-range model launches tomorrow. For households that don’t plan to keep a car for 10 years or more, this uncertainty adds financial risk.

Unknowns Around Battery Tech

It’s true that petrol and diesel cars have more parts and require regular servicing than EV. However, EVs present a different kind of problem – unknowns. There’s evidence that batteries do indeed last many years, however, battery replacement costs are relatively unknown. Some manufacturers design battery cells to be replaceable but only through the official dealers, sometimes the repair process is just conceptual. Others use designs that are so tightly integrated with the chassis that replacement may not be economically viable after the battery warranty period is over. There’s just no transparency from manufacturers at this point and not enough data to give a layperson enough assurance around long-term ownership risks. Essentially there are more questions than answers around how EVs will age and some may find the risk factor too high to consider.