How Engine Displacement (cc) Became An Irrelevant Measure For Road Tax

Will Malaysia be the last country to calculate road tax based on engine displacement?

The government puts taxes on things for many reasons – the raise revenue, to discourage purchasing of a certain product, to cut in on luxury spending. The Malaysian road tax does these three things. It raises revenue for the maintenance of public roads. It discourages the purchase of foreign vehicles with larger engines and it takes a bigger chunk out of those who spend on excessively large and powerful vehicles.

At least that’s how the system was set up to work. There’s one big problem – our entire road tax system is engine displacement based.

Displacement refers to the overall volume of air/fuel an engine’s pistons moves through its cylinders. A typical smaller vehicle in Malaysia, like a Perodua Axia, will have an engine than can displace 1 litre with its 3 cylinders (RM20/year road tax). A status symbol, like Range Rover SVR, might have an engine that can displace 5 litres with 8 cylinders (RM11,125.50/ per year road tax).

Historically, displacement has been a good measure to determine how large and expensive a car is. Larger displacement cars tended to be heavier and consume more fuel to move – indicating luxury and excess. There were exceptions, even in the old days, but generally this was true of the passenger car market throughout the 20th century and at least a decade into the 21st century.

Turbocharging

From the 2010s, things started to change slowly at first but then very quickly as European emissions standards began to tighten for passenger vehicles. Car manufacturers were put under pressure to create more efficient engines that produced fewer harmful gasses per kilometer that usually went hand-in-hand with using less fuel per kilometer. The solution was to redesign engines to extract more power out of the same drop of fuel.

Many changes came. The industry shifted from port injection to direct injection of fuel which atomised fuel into an extremely fine mist under high pressure. More sophisticated sensors and computers were installed to monitor and control air/fuel mixers in real time. However, the largest industry-wide change was turbocharging. Turbocharging allowed manufacturers to maintain or increase engine output while decreasing displacement. A 1.5-litre turbocharged Honda CR-V from 2020 produces more power and torque than a 2.4-litre non-turbocharged Honda CR-V from 2017. More importantly, when the 1.5-litre engine isn’t producing maximum power, it’s consuming much less petrol than the 2.4-litre engine by simply burning less air/fuel through its smaller capacity. All the other generational engine improvements also help with efficiency too, of course.

Once a niche of performance vehicles, turbocharging became a part of mainstream passenger vehicle market in Malaysia by 2016 when Honda introduced the Civic FC with a 1.5-litre turbocharged engine. It was only a matter of time before Proton, Nissan and even Perodua all gave Malaysians a taste of turbo under RM100,000.

As highlighted in our previous article, turbocharging leads to some absurdities when paired to the government’s current understanding of engine displacement. In that article, the topic was the fuel subsidy. In this article, the topic is the function of the tax itself – the road tax doesn’t necessarily take more from the rich nowadays.

Electrification

Another important aspect to consider is electrification. Many cars today are hybrids without even mentioning ‘hybrid’ in the name, grant or even brochure. The default engines in many staple BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Volvo and Land Rover products are feature a ‘mild hybrid’ element. These engines are also turbocharged. Electrification in this case can make a 1.5-litre engine feel much more powerful than expected due to the immediate torque offered by electric motors.

The Solution

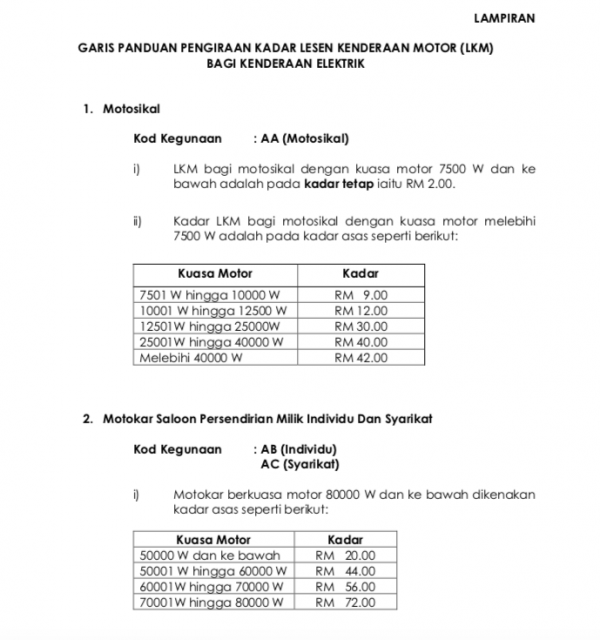

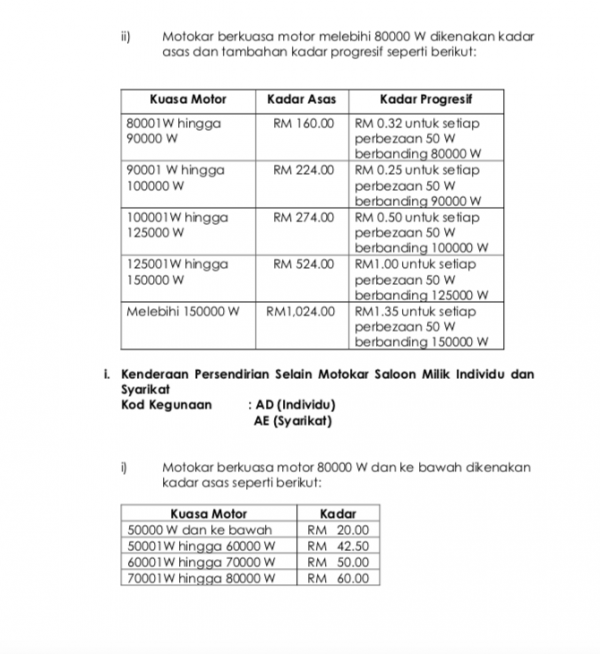

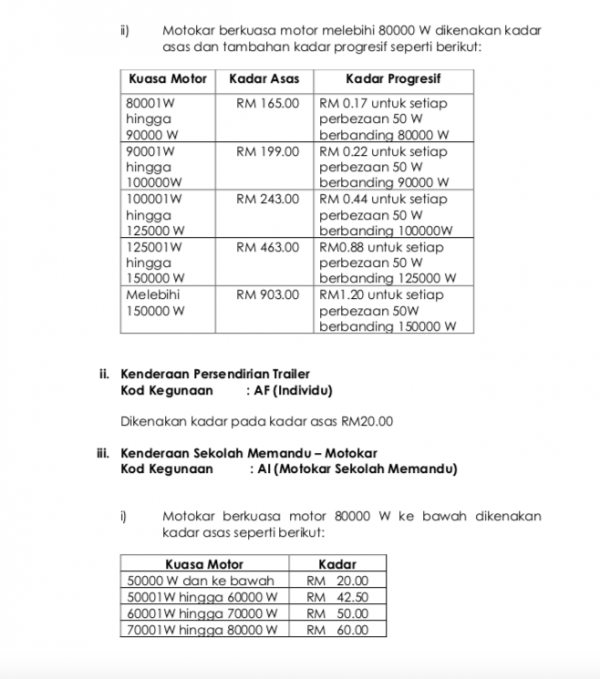

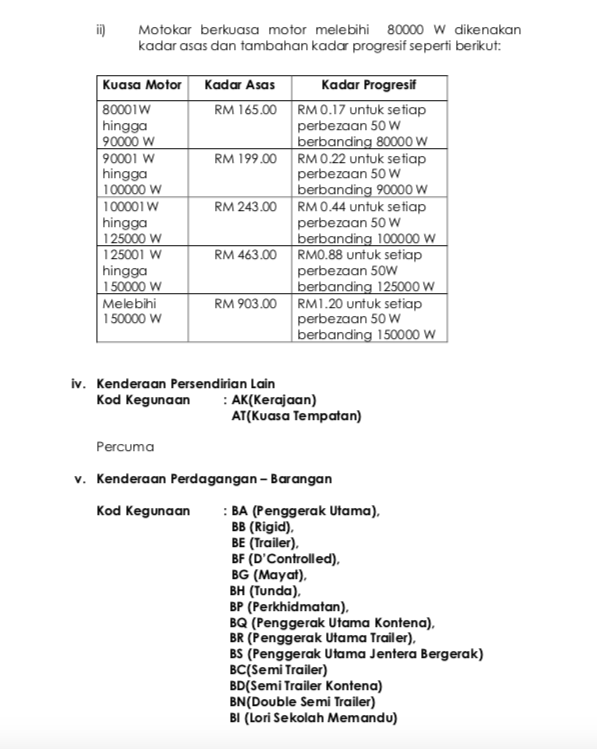

JPJ already has a new road tax calculation scheme based on power output for electric vehicles. We think the scheme is fair enough. This scheme could be extended to petrol and diesel vehicles as well and perhaps it can be improved by factoring in the number of seats or seatbelts in a given vehicle. After all, an MPV or work van with a larger engine output ought not be taxed as heavily as a sports coupé with a similar engine output. One potential issue is that grants don’t carry output information, and JPJ will have a lot of work on their hands trying to figure out what the official output of every engine they’ve ever registered is. The information may be out there, but it’s still a lot of work.

Alternatively, the government, if serious about combating pollution and getting old clunkers off the roads, could mandate an annual emissions check up that could influence the road tax rate as well. This might not be easy to implement and will be unpopular with classic car collectors and B40 Malaysians with older vehicles as well, so an output-based road tax makes more sense.